Sustainability Reporting, A Real Challenge For Data Management

Published on 2023/08/20 23:34

Julie Paumerie, CSR Director, Investance Partners

Sustainability, CSRD, CSDDD: what are we talking about?

As part of the European Green Pact, the European Union has introduced a whole arsenal of legislation (European taxonomy, SFDR regulation, CSRD and CSDD directives) designed to address climate and social issues on a European scale. More specifically, the CSRD (Coporate Sustainability Reporting Directive) and CSDDD (Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive) are designed to standardise and unify corporate social responsibility (CSR) regulations across Europe.

The CSRD requires the publication of a new consolidated report on sustainability information. This directive replaces the former declaration of extra-financial performance (DPEF) and makes a greater number of entities subject to it1.

The CSDDD, for its part, concerns the duty of care now seen at European Union level, requiring companies:

– On the one hand, to carry out due diligence, particularly on the supply chain;

– And secondly, to draw up action plans to identify potential human rights and environmental abuses throughout the company’s value chain.

– These constraints have two main objectives: transparency and uniformity of ESG (environmental, social and governance) data.

The hidden face of these regulations: the importance of understanding sustainability data

While the current state of these regulations clearly highlights the objective of transparency, insufficient attention has been paid to the challenges involved in understanding the data.

Yet understanding the substance of this data is a strategic and necessary step, and a prerequisite for reporting and for the very objective of transparency sought by these directives.

The terminology of sustainability introduces a major issue concerning data: double materiality. The concept of double materiality consists of taking into account :

– The social and environmental impact on society,

– And also societal and climatic changes that could impact the company’s business model.

The complexity created by this double materiality for the company and for the data is to bring together financial and non-financial data.

Illustration of double materiality © Official Journal of the European Union, C 209/1, COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION, Guidelines on non-financial reporting: Supplement on reporting climate-related information (2019/C 209/01)

The headache of understanding standards and identifying data

The European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG)2 has published the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) to guide stakeholders in implementing the CSRD regulations.

The ESRS can be broken down into

– Fourteen cross-sector standards, divided into 4 categories (general principles, social, environmental and governance);

– And sector-specific standards (including the financial sector).

The added value of the ESRSs is that they are aligned with the initiatives already being deployed at international level, in particular the draft standards of the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), and now even include the issue of biodiversity and ecosystems (in particular by taking into account the work of the TNFD – Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures).

This pooling of existing reference systems will make it possible to draw up an initial map of the sustainability data to be collected. The ESRSs will have to be validated by the European Commission and will be the subject of a delegated act in June 2023. As for the sectoral standards, these are still being studied and have yet to be defined for the financial sector.

At this stage, companies have to apply these standards in a context of restructuring themselves, with two levels of difficulty: understanding the standards and understanding the data to be produced.

Understanding the data to be disclosed and guaranteeing its quality: priorities that must not be neglected

As the saying goes, ‘What is well conceived is clearly expressed ’3. This quote from Nicolas Boileau applies perfectly to the challenges of the two new regulations on corporate social responsibility (CSR). Indeed, to achieve the objective of transparency for investors, companies must have real control over the data to be communicated.

The time pressure of the entry into force and application of these directives must not give way to a double risk:

– Produce data without a quality management process;

– Applying calculation methodologies that are not fully mastered.

Understanding and mastering this data is an elementary prerequisite for effectively managing a CSR strategy and ensuring real transparency for investors and customers.

For companies, this means moving away from a declarative approach, with a multitude of extra-financial data that is sometimes poorly understood and understood, to a demonstrative approach that is fully integrated into the company’s strategy. As a reminder, this data will be audited by an independent third-party organisation (OTI).

Let’s take two concrete examples where a lack of mastery of sustainability data can put a company at legal and reputational risk.

A first example of putting a company’s carbon footprint at risk:

There are two methods for carrying out a carbon balance: using financial data (accounting method) and using non-financial data (physical flows method).

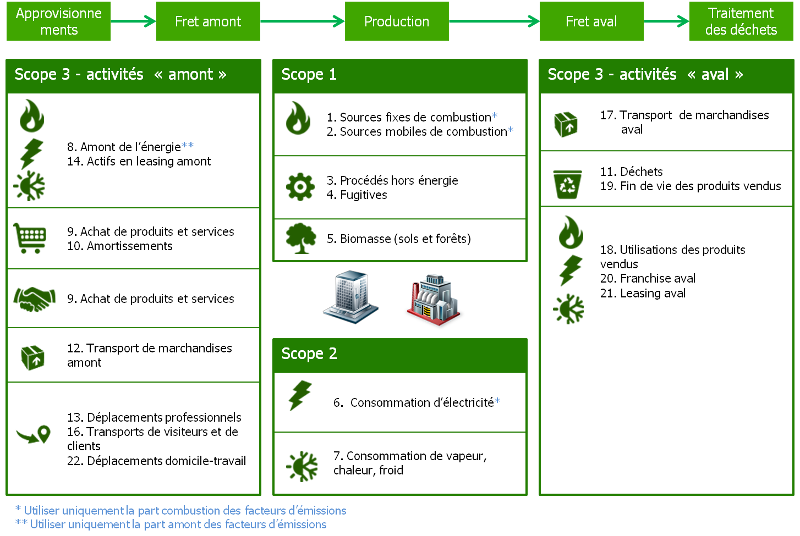

As a reminder, a carbon footprint is based on 3 scopes. The first scope refers to direct emissions linked to the manufacture of a product, particularly if the product in question requires the use of oil. All the emissions generated by this manufacturing process are included in Scope 1.

Next, Scope 2 covers indirect emissions linked to energy consumption in the manufacture of a product or service. Finally, Scope 3 calculates the other indirect emissions linked to the manufacture of products, the provision of services and the operation of the company, both upstream and downstream.

Illustration of the 3 scopes of the carbon balance © ADEME – Bilan GES website

With regard to the CSRD directive and the reliability of data, the accounting data method is not only incomplete from a regulatory point of view but also uncertain from a scientific point of view.

Firstly, from a regulatory point of view, the accounting method is incomplete: in particular, reference should be made to EFRAG’s ESRS standards4 which explain the reporting of scope 3 of a company’s carbon footprint.

By definition, the accounting method only takes into account the expenses incurred by the company. In other words, all emissions downstream of the company’s value chain cannot be analysed using the accounting method. Similarly, the use and eco-design of digital technology within a company, commuting to and from work, and the recycling of office waste are not data included in the accounts, and are therefore not included in the accounting method.

However, the accounting method can be used to identify the largest items of expenditure, which can then be prioritised for analysis using the physical flows method.

In addition, it has been shown that the accounting method is 80% less effective than the physical flows methodology, since the accounting method does not include geographical or temporal data. In addition, the physical flows methodology allows greater exhaustiveness of the data collected and greater precision by avoiding any estimates.

For example, a company’s investments analysed using the accounting methodology would only take into account the weight of the investment in euros, which would then be converted into eqCO2. However, the physical flows method would integrate the GHG emissions of the companies in which it has invested into the company’s carbon footprint. This enables the company to effectively manage its low-carbon strategy by identifying its most polluting partners.

Added to this is the fact that, against a backdrop of legislation on greenwashing (climate and resilience law, 2021), the reliability of the data transmitted is extremely important and requires constant vigilance in view of the growing number of disputes on these subjects.

The second example concerns the data to be collected on human rights from suppliers and subcontractors

Collecting data on potential human rights abuses by a company’s suppliers is complex for a number of reasons:

The first is the opacity of the value chain. The first is the opacity of the value chain. The company must be able to monitor its suppliers, who may themselves use subcontractors. The company will need to have the means to ensure complete traceability of its value chain without any break.

The second is the evolution of data as a result of unstable geopolitical contexts. Human rights risk analysts must be able to interpret this data in the light of a context that requires constant vigilance.

The third is the very definition of the data to be collected according to the sector. A classification must be made in order to be as operational as possible. This requires expertise to identify the most likely potential impacts, taking into account the specific characteristics of each business, company size and location.

The fourth difficulty we have identified is the disparity of data. KYS (know your suppliers) questionnaires will be based on both qualitative and quantitative data. We therefore need to be able to ensure the consistency of these different types of data.

And finally, the last complexity criterion is linked to a shift in responsibility. For the company, it is not simply a question of asking its suppliers for certification or a label to prove compliance with CSR principles, but of proving the constant due diligence carried out on its partners and bearing the responsibility for this proof.

Photograph © REUTERS. The collapse of Rana Plaza in 2013 led to the adoption in France of the law on the duty of care of parent companies and principals towards their subsidiaries and subcontractors around the world. The CSDDD (European duty of care) is directly inspired by the French law.

Data governance: a necessary and minimum means of meeting the challenges of sustainability reporting

Given the variety of sustainability data to be produced, many departments (HR, Purchasing, Compliance, Logistics, Marketing and Communications, Investments, Retail, CSR, etc.) are concerned and involved at two levels:

– In the operational integration of ESG data into their own processes

– And in the interaction with other departments as a result of shared ESG data.

Firstly, this requires the various departments to be trained in sustainability issues and to be familiar with the ESG data within their scope. For data that is shared, the challenge is to understand the interactions with other departments and to identify the owner of each piece of data.

Faced with this complexity, organisations need to be able to rely on operationally structured data management, at the very least through the definition of ESG data governance for the company as a whole. It is therefore up to the company to have a chief data officer, for whom ESG data management becomes a major and compulsory task.

Furthermore, while the implementation of ESG data governance principles is a prerequisite, its operability can only be based on appropriate technical resources that are integrated into the existing IS, in particular for :

– To have a centralised view of ESG data, facilitating its control and guaranteeing the expected level of quality,

– Identify who is responsible for the data (data owner) and ensure that reporting requirements are properly managed.

The result of this approach is a preliminary analysis of the regulations in order to identify all the data required, the common nature of some of this data, its correct definition and understanding, and the ‘golden source’ of this data.

Without dedicated and effective data governance and appropriate technical resources, the implementation of the CSRD and CSDDD regulations will appear all the more complex and risky given the challenges of sustainability reporting.

Références

- In formal terms, the number of legal entities subject to this requirement has been greatly increased. The entities concerned are those that meet two of the following three criteria: a balance sheet of 20 million euros, a turnover of 40 million euros and 250 employees. Subsidiaries, on the other hand, are not subject to the publication obligation when the parent company publishes a consolidated report. This does not exempt subsidiaries from reporting non-financial data to the parent company. Subsidiaries are therefore subject to the obligation indirectly. Transparency obligations also apply to foreign companies operating in the European Union via a branch or subsidiary. The extraterritorial dimension of this directive, justified by the link to the European Union, underlines the European Union’s desire to be a standard-setting leader in CSR. ↩︎

- EFRAG is a private association established in 2001 with the encouragement of the European Commission to serve the public interest. EFRAG extended its mission in 2022 following the new role assigned to EFRAG in the CSRD, providing Technical Advice to the European Commission in the form of fully prepared draft EU Sustainability Reporting Standards and/or draft amendments to these Standards. Its Member Organisations are European stakeholders and National Organisations and Civil Society Organisations. EFRAG’s activities are organised in two pillars: A Financial Reporting Pillar: influencing the development of IFRS Standards from a European perspective and how they contribute to the efficiency of capital markets and providing endorsement advice on (amendments to) IFRS Standards to the European Commission. Secondly, a Sustainability Reporting Pillar: developing draft EU Sustainability Reporting Standards, and related amendments for the European Commission.” (Source : EFRAG Today – EFRAG. www.efrag.org/About/Facts#subtitle1.) ↩︎

- « Chant I », L’Art poétique, Nicolas Boileau, éd. Aug. Delalain, 1815, p. 6 ↩︎

- ‘The principle behind this disclosure requirement is to provide an understanding of the GHG emissions that occur in the company’s value chain beyond its Scope 1 and Scope 2 GHG emissions. For many companies, scope 3 GHG emissions are the main component of the GHG inventory and a significant driver of their transition risks. 46. The disclosures required by paragraph 44 shall include GHG emissions from the material categories in scope 3 and shall be presented in the form of a breakdown of GHG emissions from (i) upstream purchases, (ii) downstream products sold, (iii) freight transport, (iv) travel, and (v) financial investments.’ ↩︎

Julie Paumerie

Julie Paumerie is head of the CSR department at Investance Partners and a CSR consultant and doctoral student at the firm. She is responsible for developing the firm’s CSR and ESG offerings and helps financial institutions manage their sustainability risks, regulatory compliance and CSR strategies.